The hyperbole of the “smart refrigerator” has been propelled to the mainstream rhetoric of the IoT connected future, in part because it seems many of the pieces of such a fanciful device are coming together. The idea of a fridge that can measure the consumption of items and automatically re-order them for home delivery “seems inevitable” given we have partially-automated re-ordering through Dash buttons, other IoT devices to track product waste, door locks that let through delivery companies, and internet-connected refrigerators.

Of course, even if all the pieces of the puzzle seem to be there, a number of challenges actually remain. For example, which items do people want re-ordered before they run out (e.g. milk?), which do they not care about running out, what of the human desire for variety, and what about sporadic events such as holidays?

In our work, to be presented at CHI 2019, we set out to understand the contingencies of life that may impact the consumption of everyday items in the home. In turn, we address how future systems could potentially address these contingencies in design. In this post I will summarise our study and some of the headline findings. For a more detailed insight, I encourage you to read the paper (free to read).

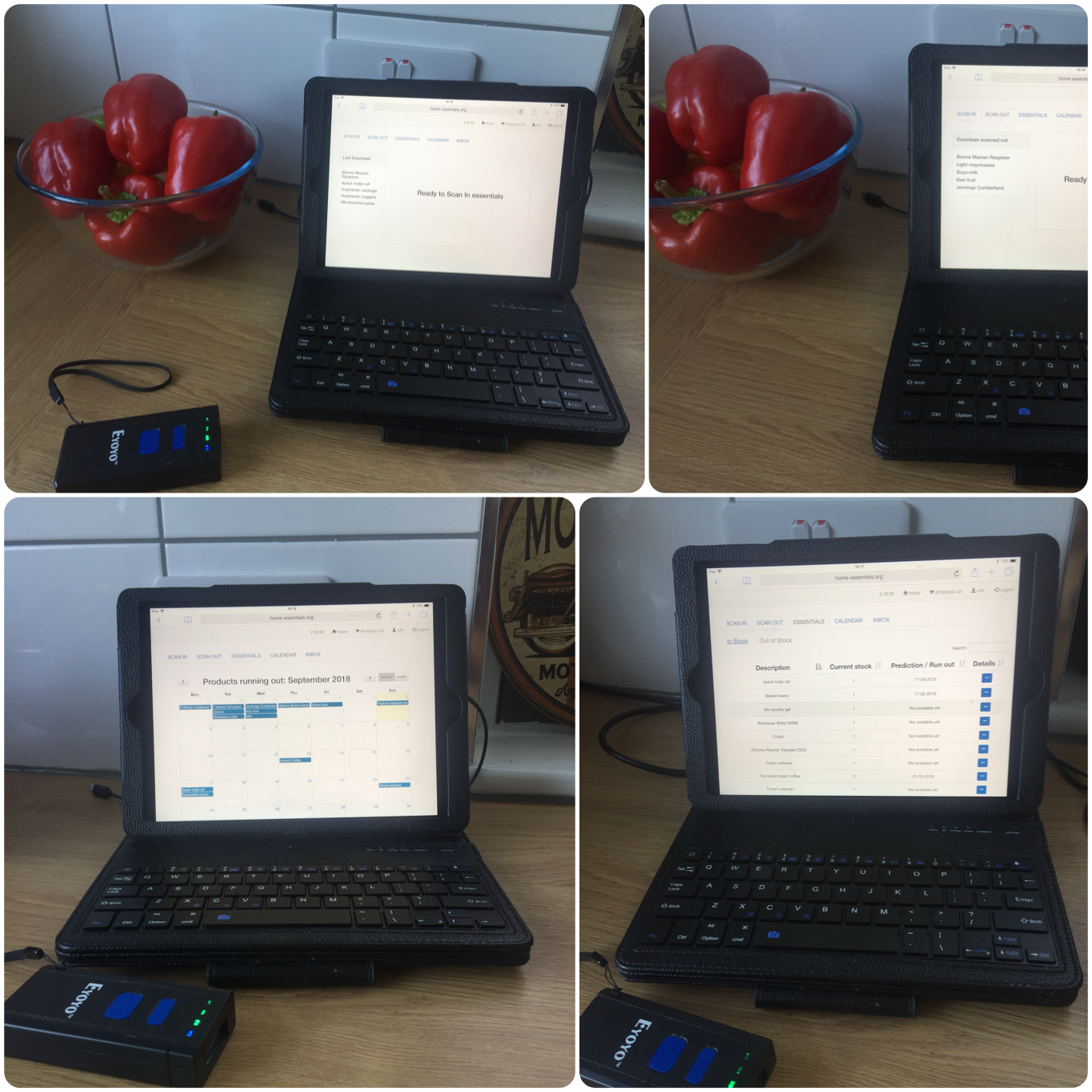

An iPad running our tracking app with a Bluetooth barcode scanner

To understand more about how items were consumed in homes, we built a simple-to-use web-based tracking application, designed to be used on an iPad. We recruited ten participant households to input twenty (or so) “essential” household items into the system. This was done by asking users to scan the barcode on the item when they bought it and scan it again when they used up–or threw away–the item. This would give us a “time-to-consume” for the item. We recruited the households for a two-month study, and throughout the study attempted to predict their consumption of items based on an average of previously logged time-to-consumes.

We chose a simplistic prediction model not to be naīve, but because the purpose of this work was for the tracking system to serve as a probe to understand how households deal with and explain the innacuracies.

Our predictions fared differently for different items: milk for example was easier to predict but other items less so. When our predictions were more than one day out, the system would ask the participant for some reflection on to what could have caused this.

We also interviewed participants before, during, and after the study. These interviews allowed us to further elicit reflections on using the system, their experiences of tracking their items, and how they think an autonomous reordering system could adapt to their lifestyle.

The paper’s findings are made up of this prediction data, households’ reasons of why predictions were wrong, and insights from our interviews.

Firstly, and unsurprisingly, we saw a variation in the use of the system based on the demographic breakdown of the house (e.g. single-occupancy homes compared with homes of families with multiple children). The larger the family, the greater frequency with which they scanned items in and out of the system.

Prediction accuracies correlated significantly with the time-to-consume, or in other words, the longer it would take to consume something, the less accurate our predictions were. This could perhaps be partially explained by our study length, but still remains a factor to consider in predictions.

Additionally, the more times an item was consumed, the more accurate our predictions were, but only marginally, suggesting simplistic computational predictions are generally inaccurate.

When our predictions were wrong (either early or late), we asked participants for a quick response as to why that might be. Our analysis of these responses resulted in eight categories including: normal use, sporadic events, routine change, and location. In many of the cases, participants simply remarked that they identified no reason for the prediction error (normal use). Other reasons for the innaccuracy were explained as a result of one-off (sporadic) events such as dinner parties, routine changes such as the seasonal variation, and issues like people forgetting to use an item because it was placed out of sight (or it being left in a convenient location thus was used more quickly).

Overall, through the interviews, categorisation of household’s responses, and analysis of the prediction data, we reveal and systematise the reasons for why the everyday use of household products is variable. In the paper we unpack further issues relating to prediction consumption, such as product equivalency (e.g. are two different varieties of apple the equivalent to the household members?).

The resulting design challenge we highlight is how to deal with these contingencies in design (or: how does the system deal with uncertainty over which actions to take?). If we are to have to have autonomous IoT devices that track our consumption and re-order products when needed, how should they function given the variability of everyday life.

As we see it, we propose a number of (overlapping) approaches, based on existing literature, that such a system could take to predicting and acting upon consumption in the home:

Overall, what our work does do, is bring to the fore the variable nature in which people consume items in the home, and the challenges that any future system may face in attempting to predict and act upon consumption in the home. We propose a number of strategies in the paper for how designers might right to this challenge.

Originally posted at https://www.porcheron.uk/blog/2019/04/27/predicting-consumption-in-the-home/

https://www.porcheron.uk/blog/2019/04/27/predicting-consumption-in-the-home/