The recent growth in popularity of Voice User Interfaces (VUIs), from smartphone assistants (e.g. Siri) through to smart speakers (e.g. Amazon Echo) has led to a recent resurgence of research in HCI that examines the design and use of novel technologies such as ‘natural language’ interfaces. A tried and tested method in research with natural language interfaces is to make use of the Wizard of Oz approach, presenting the user with what seems to be a fully-functional system, when in reality parts of the ‘intelligence’ of the system is secretly human-powered.

The Wizard of Oz method proffers designers and researchers the ability to develop medium-fidelity prototypes1 that can be used for the exploration and testing of ideas as part of iterative design processes and research, and feeds into a number of different forms of analyses, from qualitative Conversation Analysis2 through to quantitative task performance analysis3, as well as product development. We’ve used it recently too.

To enable us to undertake these forms of studies, I developed a Python-based application for simulating a modern VUI. The app has only been tested on macOS, but should work on Windows and Linux-based systems. The app, called NottReal (a pun on Nottingham), includes support for multiple voice simulation systems and includes an optional ‘Mobile VUI’-like window. It also includes basic speech recognition support.

NottReal starts with a prompt to open a configuration or create a new one. NottReal configurations are a set of files in a directory where the directory has an nrc file extension. On macOS, these are shown as a package thus to access this directory in Finder you’ll have to right-click and select Show package contents. The configuration is spread across a number of files—refer to the README to how to set up each file.

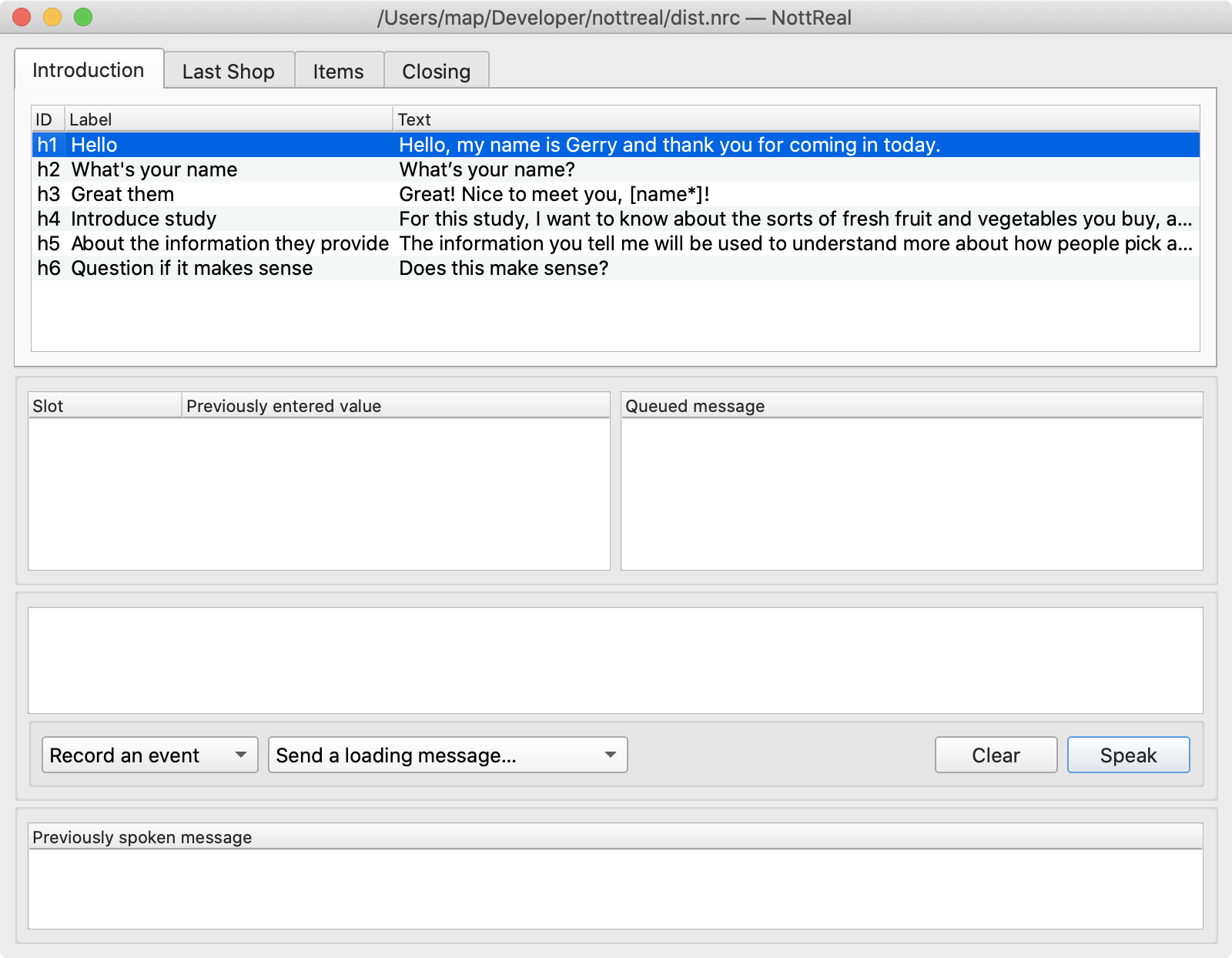

After this, you are shown the Wizard Window. This is the main control panel for Wizards, and includes lists of prepared messages. These are messages that can be quickly sent to a participant by double-clicking. Lists of prepared messages can be split over tabs—we’ve used this to segment experimental conditions or for different stages of the study.

These prepared messages can contain slots, in [square brackets], that have to be replaced when sending the message. For example, it could be a participant’s name. Previously used slots are displayed in a list in the window. NottReal can automatically track these substitutions if the slot has an asterisk at the end of its name, e.g. [name*], such that all subsequent uses of the slot automatically replace with a previously set value.

By default, NottReal will not send a message to a voice simulator while it is speaking. This allows you to queue up messages to send. The application shows this queue as a list in the UI.

Custom messages can be typed and sent at any time, as can messages that show a loading animation in the Mobile VUI (more on that below). The application also logs all messages sent in a data file, but you can optionally log additional information (e.g. a Wizard’s decision taken at a certain point).

Finally, previously sent messages are shown at the bottom of the UI as a list.

The menu includes a number of options, including enabling voice recognition, choosing the input source, showing an output window, and selecting the voice synthesis library.

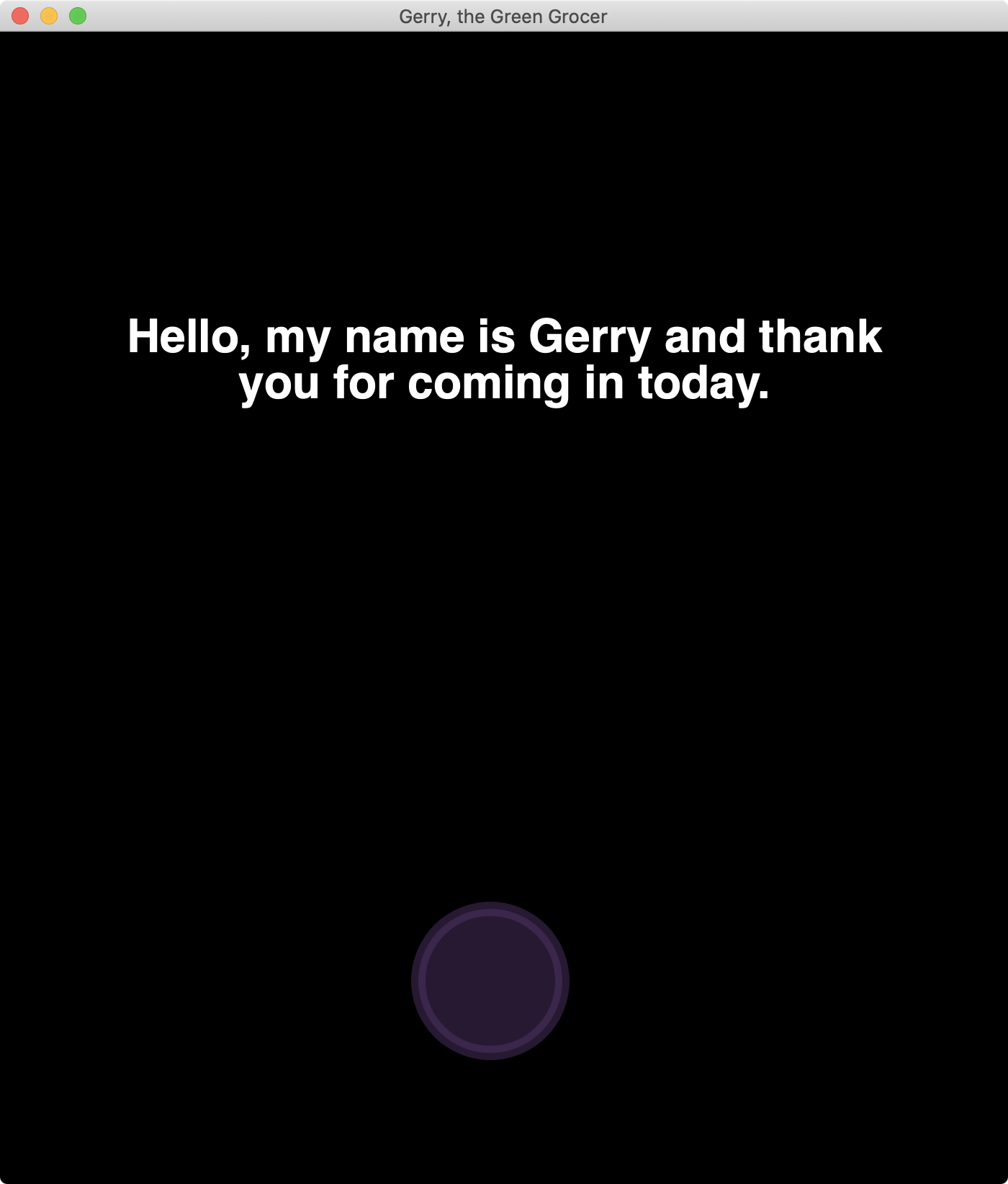

NottReal is designed to support custom simulated outputs, and one such visual output is included. This looks sort of like a basic Mobile VUI, with (by default) a black portrait window, with white text and an ‘orb’ that shows the state of the VUI4.

This orb supports four states: resting (i.e. a static circle), busy (a loading/computing animation of a white ring with a rotating wedge missing), listening (a flickering orb based on the volume level of a microphone, shown in the figure), and speaking (a glowing ring that fades in and out). NottReal automatically switches this orb that is being shown in this window. For example, it will show the speaking orb while the voice synthesis library is ‘speaking’ and will switch to either the resting or listening orb afterwards5. The Wizard can also control which orb is displayed manually from the menu or with keyboard shortcuts.

We have made this window full-screen on a second monitor connected to the Wizard’s computer in our studies. In one study, we used a 30m VGA cable so the Wizard could be in a separate room, or we’ve simply been behind a screen and controlled the study in the same room. This second window also works great on an iPad display with Sidecar in macOS 10.15 Catalina6.

This output has been useful to minimise the effects of participant’s understanding of the simulated voice (e.g. for second language speakers), and also when we have wanted them to look at a camera throughout the study.

NottReal is available for download as an application bundle for macOS or as python source from GitHub. If you’re using the app on Windows or Linux, you will have to follow the instructions in the README for installing the dependencies.

The project is open source under the MIT Licence. Contributions in the form of bug reports and pull requests are very welcome! If you’re a Windows developer, bundling support is appreciated!

If you use NottReal in your research, please let me know. It’s always rewarding when someone uses a piece of software you’ve made. If you wish to cite it, please use the reference at the end of this page.